Archived Content

This page is archived and provided for historical reference. The content is no longer being updated, and some of the information may have changed over time and could be outdated or inaccurate.

By William (Bill) Elwood, Ph.D.

Culture informs all human behavior: in it we exist as social animals. Perhaps because culture is inescapable it seems also elusive as a definable construct, and the culture of scientists recoils from a variable it believes it cannot grasp … almost literally.

Researchers rely on a set of proven variables. Scientists study cells and variables. Healthcare providers treat individuals. Cells, as well as the myriad of social and behavioral variables whose functioning and interactions researchers strive to understand, are, at once, expressions of and highly influenced by the surrounding culture. One’s history is written in one’s body, we have come to learn, is not a mere metaphor. The culture of scientific research and of medicine focuses on the individual.

A study that targets people by ethnic, racial, or sexual identity naturally would assume that a population’s beliefs and behaviors are uniform. The same assumption sometimes appears in studies that target members of a language group—but native Spanish speakers know that what and how people say something on the Isla de la Juventud differs from what people say in Barcelona, or in any of the many cities around the world named San José. Just as language differs across a continent and the world, so do the knowledge and beliefs of what constitutes health, illness, and wellbeing.

Another problem with studying the effects of culture in health, healthcare and health-related behaviors is the limiting views of the researchers, who are historically coming from a majority and privileged group, which they tend to construct as the measuring stick. A majority’s culture is not culture, but norm, as Marjorie Kagawa-Singer and colleagues aptly describe in their recent article:

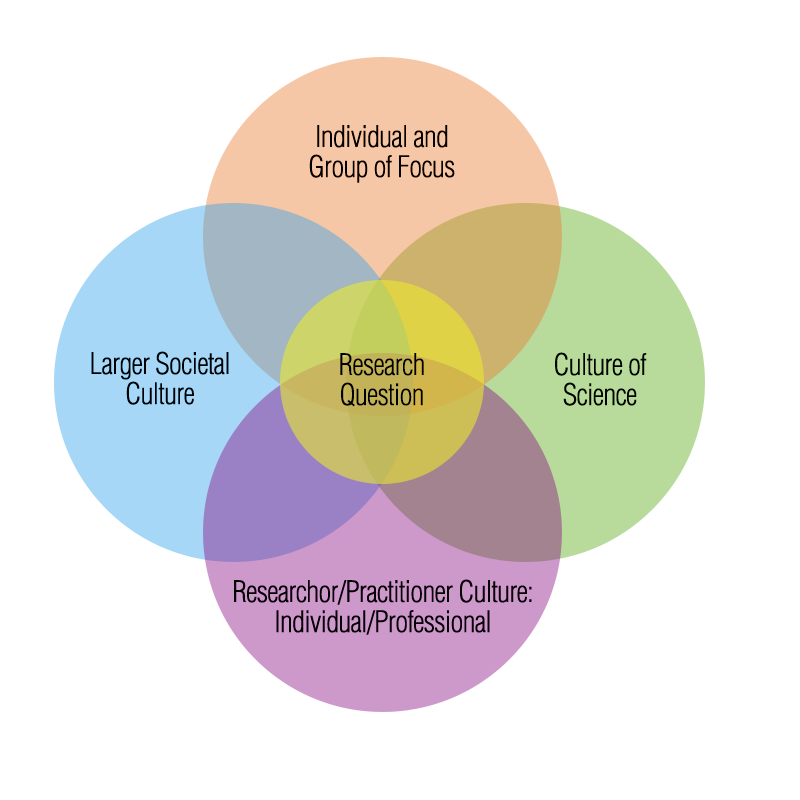

"Notably, another tacit assumption in health research appears to be that only those being studied have culture (Heurtin-Roberts, 2009), which renders researchers using the lens of the dominant culture to ignore the influence of their own culture and the culture of science on the research processes and populations of focus. Also implicit in studies of diverse populations is the view that the multiple cultures existing in most geographic areas function in isolation from each other. The most common results of this viewpoint are: 1) the dominant U.S. culture does not recognize that the assumptions that underlie the scientific endeavor reflect their own norms and, 2) the culture of science often does not acknowledge its own influence or the dynamic interplay among and within cultural groups, the blending at the edges of each, and, ultimately, the impact the culture of the group with the greatest power has on the populations of focus."

In short, measuring culture and its influence on health and wellbeing isn’t easy. That’s why the NIH Office of Social and Behavioral Sciences Research (OBSSR)funded University of California, Los Angeles’s Kagawa-Singer to lead an expert panel to develop a framework that researchers can use to study how cultural processes influence health-related behaviors.

Thirty researchers were invited to become members of the Expert Panel by the project officer from the OBSSR, the funding agency, and the principle investigator (PI) and co-PIs of the study. The selection criteria for Expert Panelists were:

- Substantial experience studying culture and health,

- A significant history of NIH funding, and

- Diverse disciplines in training and work settings.

Panelists were trained in seven different disciplines: psychology (3), psychiatry (1) medicine (6), anthropology (11), sociology (6), public health (4) and nursing (2). Most held faculty appointments in departments other than that of their doctoral-level training. Expert Panel members also had expertise in both qualitative and quantitative methods and extensive experience conducting health research in a wide range of cross-cultural, linguistic, national, and international contexts.

The project, and the July 2016 Social Science & Medicine article, suggest researchers perceive culture as a shared framework or lens through which group members “see” reality and through which individuals and groups collectively experience and interpret their experiences. Culture provides beliefs, attitudes, practices, spiritual and emotional explanations people use to create norms of ways of being in social settings. This set of “cultural tools” enables group members to make sense of their world and to provide a sense well-being and identity with one or more social network.

The project, and the July 2016 Social Science & Medicine article, suggest researchers perceive culture as a shared framework or lens through which group members “see” reality and through which individuals and groups collectively experience and interpret their experiences. Culture provides beliefs, attitudes, practices, spiritual and emotional explanations people use to create norms of ways of being in social settings. This set of “cultural tools” enables group members to make sense of their world and to provide a sense well-being and identity with one or more social network.

Though the framework is more extensive, the article and online text recommend that researchers ask themselves the following six questions when planning a research study that involves groups of human beings:

- Is the rationale for the inclusion of culture clearly articulated in the problem statement?

- Does the study articulate a clear definition of culture?

- Are salient theoretical constructs known? Are the cultural constructs equally known equally well?

- Do the theoretical and cultural constructs relate with one another?

- Do the researchers understand how the target population’s cultural constructs influence how these people understand the health-related issue?

- Are there existing measures that relate across cultures?

There is a culture of scientific research—actually, there are cultures of research depending on your major in college and doctoral-level training! There is an equal, if not larger, number of cultures associated with everyday life. The cultural framework for health provides a resource so researchers can infuse their studies with the cultures of their research participants as well as the culture of scientific inquiry.

References

The Cultural Framework for Health

VIDEO: Culture, Research, and Health Outcomes Panel

Culture: The Missing Link in Health Research

Transforming Culture and Research: Operationalizing Culture and Its Relationship to Health and Wellbeing Outcomes